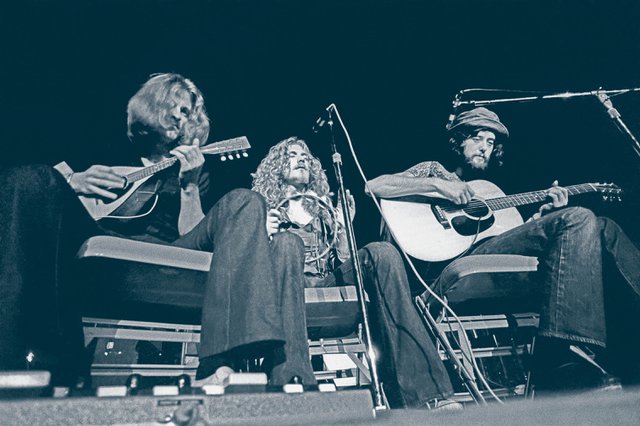

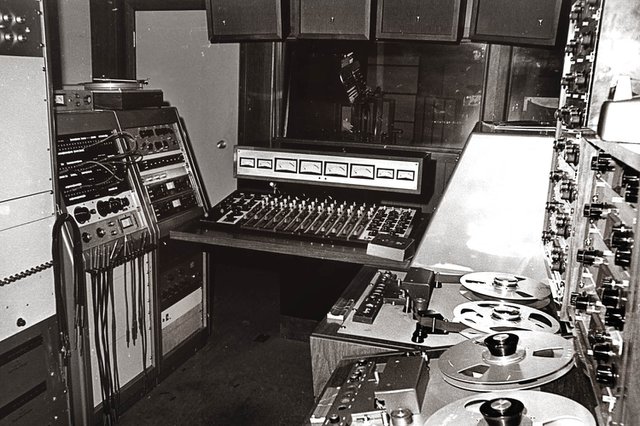

On a bitterly cold morning in January 1971, guitarist Jimmy Page, 26, singer Robert Plant, 22, bassist/ keyboardist John Paul Jones, 24, and drummer John Bonham, 22, arrived at Headley Grange, Hampshire, to find the Rolling Stones’ mobile studio already waiting for them in the driveway.

With them was a young engineer by the name of Andy Johns, brother of Glyn, who had worked on the first Zeppelin album, piano player Ian Stewart, formerly piano player and jack-of-all-trades for the Rolling Stones, and known to all and sundry as Stu, along with a small road crew.

Plant and Page, in the grip of an intense and productive creative union, fell into that group of artists whose muse was susceptible to their surroundings. The damp, cool manor, with its bleak history, surrounded by the bare winter trees, affected them quickly.

“Most of the mood for the fourth album was brought about in settings we had not been used to,” Plant later reflected. “We were living in this falling-down mansion in the country. It was incredible.”

That opinion, though, was not universally held among the group: “It was cold and damp,” recalls Jones. “We all ran in when we arrived in a mad scramble to get the driest rooms. There was no pool table or pub. It was just so dull."

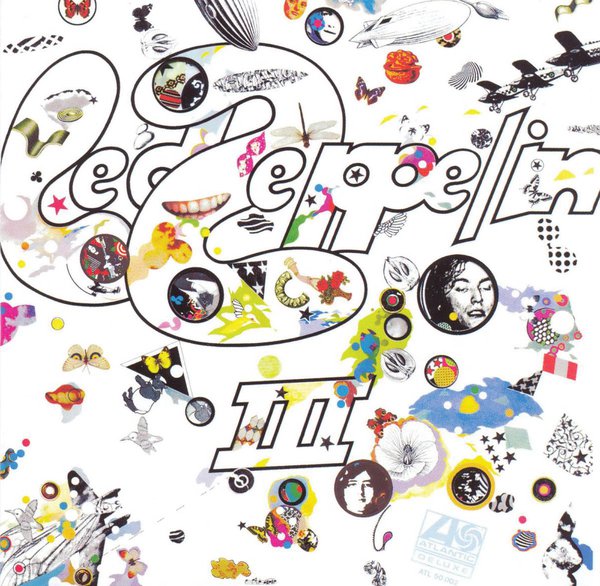

So it was that, 140 years after it was ransacked by several hundred mad rioters, Headley Grange took up its role in the making of the most famous and most imitated rock record in history. By the time the band began to think seriously about material for their fourth album, Led Zeppelin, it seemed, could do almost what they wanted. It didn’t matter what the critics said, Zep were now big enough to take the knocks.

Manager Peter Grant was not given to taking chances, however, and in a typically farsighted move, he effectively took the band off the road during the latter half of 1970, in order to allow them the space they needed to come up with something fresh again.

Patricia Ecker Page (RIP)

in News

Posted

https://www.facebook.com/jimmypage/photos/a.10150938033972612/10158727464467612/